Basics of Buddhism

Shinnyo‑en is a Buddhist tradition founded in Japan. It is a lay form of Mahayana Esoteric Buddhism. Spiritual practices in Shinnyo‑en are focused on cultivating the natural goodness or “buddha nature” within ourselves. The tradition draws inspiration from a set of teachings called the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, often called the Nirvana Sutra, and emphasizes “meditation in action”—the development of qualities such as empathy, loving kindness, and compassion by practicing them in relation to others amid the ordinary circumstances of daily life. The path to peace and happiness cultivated at Shinnyo‑en is founded on our connection with others and rooted in a profound sense of shared humanity.

Buddhism

What is Buddhism?

“Buddhism” is the English word for buddha-dharma, a Sanskrit term that refers to the teachings, or “dharma,” revealed by the historical Buddha. In ancient India, where the Buddha lived and taught, the word dharma was used to refer to both universal truths about the nature of reality and a way of living one’s life in harmony with those truths. Buddha-dharma refers both to spiritual truths that the Buddha realized and taught to others and to living a life in harmony with the nature of the universe.

The central truth at the heart of the Buddha’s teaching is that everything we know and experience is connected—this world, the trajectories of our lives in it, and we ourselves are all related to one another through an imperceptible web of causes and effects that stretches infinitely into the past. To live in a way that reflects the interdependent nature of our lives, we must let go of self-centered ways of thinking and acting, recognize ourselves and others as mutually connected, and live our lives in a way that helps others and avoids harm.

What is a buddha?

Buddha means “awake” or “awakened one” in Sanskrit. It describes a person who has, through spiritual practice, removed delusion, egotism, and the suffering they produce from their mind. When a buddha develops a clear understanding of reality, that knowledge undermines the delusions that obscure the natural clarity and goodness within the mind, and they are then able to shine forth and express lovingkindess to the fullest. This state is referred to as “awakening.” Like a dreamer in a dream, we mistake our own projections that we ordinarily experience for reality. “Buddha” can refer specifically to (a) the historical founder of Buddhism (also called Shakyamuni or the Buddha), (b) to the state of awakening itself (of which the Buddha is a manifestation), or (c) to any person who has achieved that state of awakening.

Who was the Buddha?

The Buddha was born over 2,500 years ago as Siddhartha Gautama, a prince of the Shakya clan that ruled a small principality in what is present-day Nepal. Despite his comfortable royal status, Siddhartha was deeply disturbed by the suffering he witnessed in the human condition. In his late twenties, he decided to renounce his kingdom and family life to devote himself to a life of spiritual practice. He hoped to understand what causes living beings to suffer and to find a means to true peace. After six years of intense spiritual practice as a wandering monk, Siddhartha finally understood suffering, what causes it, that it can be ended, and the means for doing so. He spent the rest of his life, about fifty years, teaching others the dharma that he had discovered, becoming renowned as Shakyamuni, “Sage of the Shakyas.”

What did the Buddha Teach?

Conditioned Existence is Suffering

The Buddha taught that everything that exists depends on prior causes and conditions, including both the external world of physical matter and the inner world of personal experiences. Just as prior states and movement of matter deep in the cosmic past gave rise to the state of the universe as we collectively experience it in the present, so too did states and movement of mind prior to this life give rise to our unique personalities and lives as we individually experience them now. The movements of our thoughts, words, and actions are what the Buddha called karma, or “action.” The Buddha taught that living beings are reborn according to their karma when they die. From the Buddhist point of view, the happy and unhappy events and experiences that occur throughout our lives are all brought about by our previous deeds. This state of existence, conditioned by karma, is characterized throughout by suffering of one kind or another: encountering experiences we do not want and being parted from those we love, rising and falling in status, being born, growing old, and dying again and again without knowing why our lives turn out the way they do.

The Cause of Suffering

What ultimately causes us to suffer, the Buddha said, is delusion. Delusion refers to perceiving the world in a way that is not how it really is and reacting to it in misguided ways that only strengthen the delusion and produce more suffering. Due to this ignorance, our lives and the experiences and events that fill them appear more real and reliable than they actually are. Friends, loved ones, and pleasant experiences appear to be truly beautiful and pleasurable sources of happiness, and we develop attachment to them. But when pleasant experiences go on too long, the pleasure fades, turning to disappointment. Or when we are parted from those we’ve grown attached to, our attachment produces pain and sadness. Similarly, enemies, hostile people, and difficult experiences appear to be truly ugly and unpleasant sources of misery and obstacles to happiness, and we develop anger in response to them. Extreme anger can even cause us to harm those we love the most, a source of deep regret. Unaware of the true nature of the events that form the ups and downs of our lives, constantly vacillating between happy and unhappy experiences, tossed by the rising and falling waves of our own karma, we think “How could this happen to me? I don’t deserve this!” Lost in the fog of such delusion, clinging to friends, lashing out at enemies, and showing indifference to the plight of strangers, we continue to carelessly produce bad karma, unwittingly perpetuating the cycle of our own suffering.

The End of Suffering

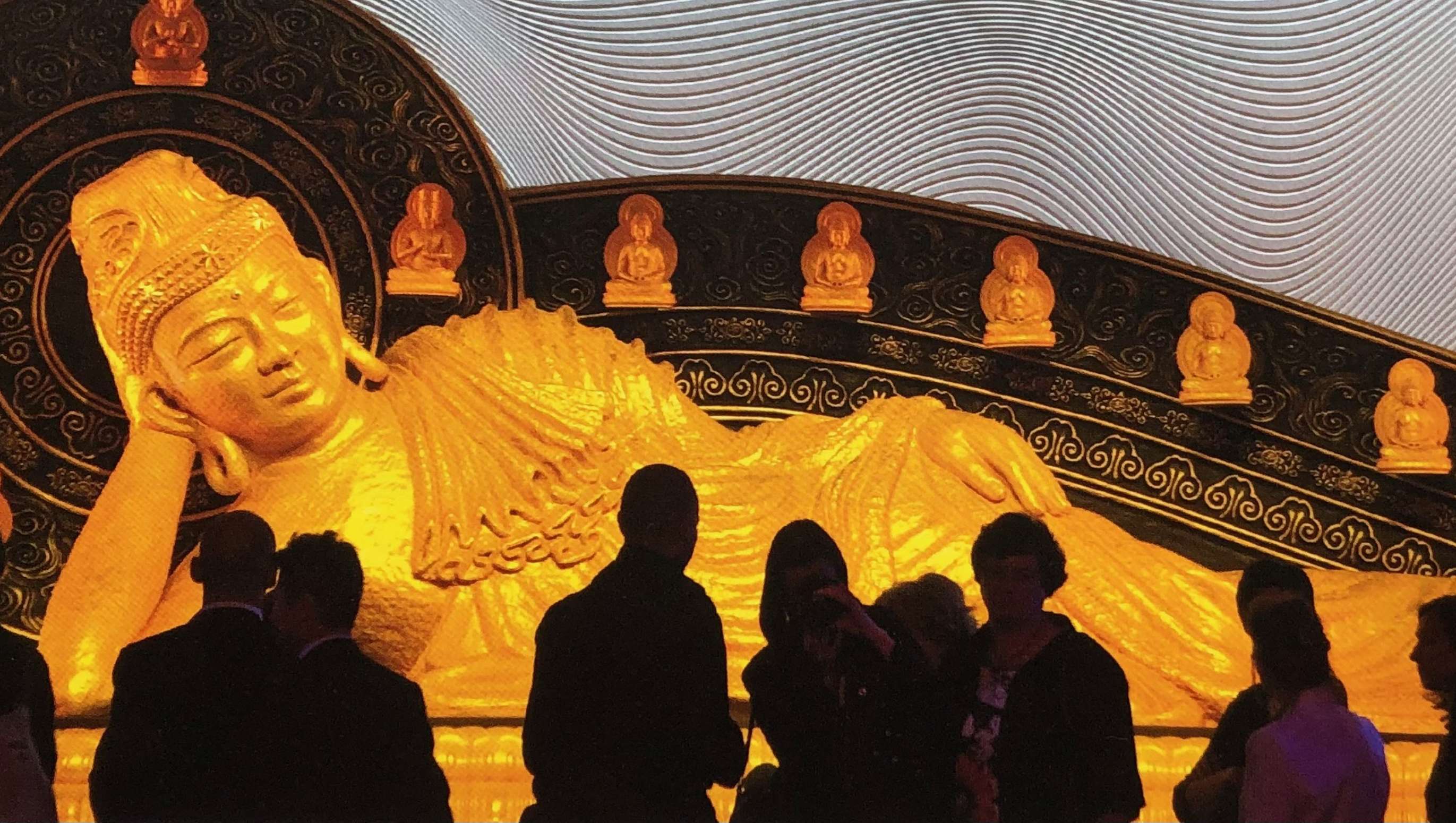

The Buddha found that it is possible to break the cycle and gain lasting peace. Since the delusion at the root of suffering is a misperception of reality, we can eliminate its cause by seeing things as they really are. Through heroic effort and dedicated spiritual practice, the Buddha was able to gain an irreversible perception of the nature of reality, causing every trace of delusion in his mind to disappear. The resulting state of mind, suffused with wisdom that unerringly understands reality, brimming with compassion for all living beings, and utterly at peace, is called nirvana, a Sanskrit word that means “extinction (of delusions).” Although the subjective state of nirvana cannot be adequately expressed in words, it is described as a state of transcendental bliss in which one’s mind has become one with the nature of reality. Since the nature of reality permeates everything, a buddha in nirvana is said to permeate all reality as well, and is therefore thought of as “ever-present.”

The Way to End Suffering

The Buddha taught a great variety of spiritual practices in order to help others understand the nature of reality and attain the same peace he attained. All Buddhist practices fall into three categories: practices of integrity, meditation, and wisdom. To begin with, the Buddha taught that we must act with integrity, neither wishing nor causing any harm to other living beings and helping them in whatever ways we can. By cultivating such discipline, we grow generous and patient with others, and develop perseverance in our practice. As the intensity of attachment and anger wane with practice of moral integrity, one’s heart and mind grow calm. Next, the Buddha taught that we must practice meditation, the intentional cultivation of mental concentration and serenity, and of spiritual qualities like equanimity, love, and compassion. Finally, as our clarity of mind and ability for sustained contemplation develop, the Buddha taught that, in order to eliminate ignorance, we must cultivate wisdom by turning our minds to examine the nature of reality itself. These three practices—integrity, meditation, and wisdom—gradually undermine the delusions within one’s mind until the ignorance at the root of the cycle of suffering is eliminated and one attains awakening.

Mahayana

Throughout his teaching career, Buddha Shakyamuni taught a variety of paths of practice, tailored to the needs, motives, and personalities of his many disciples. For those motivated by an intense sense of renunciation and a desire to escape from the cycle of suffering as soon as possible, he taught an “individual vehicle” system of practice. And for those motivated by an intense sense of compassion and an altruistic desire to free others as well as themselves from suffering, he taught the Mahayana, or “great vehicle” system of practice. Whereas the individual vehicle Theravada system focused almost exclusively on a monastic form of practice to attain awakening and inner peace, the Mahayana system provided both lay and ordained forms of spiritual practice. Today, Mahayana Buddhism is prevalent in East Asian countries like Tibet, China, Korea, and Japan, and individual vehicle Buddhism is prevalent in Sri Lanka, Burma, and Thailand in the form of Theravada Buddhism. Both forms of Buddhism are practiced throughout the world.

The ideal form of practice to which Mahayana Buddhists aspire is that of the bodhisattva, which literally means “a buddha-to-be.” A bodhisattva embodies the joy of being in community with others through their altruistic spirit of pursuing enlightenment for the benefit of all living beings. Bodhisattvas vow to work tirelessly for the benefit of others and not to enjoy the fruit of nirvana until all others have been shepherded to awakening themselves. They show no discrimination between friend and foe, are always willing to respond to a person’s true needs, and exemplify the love, compassion, and wisdom of a parent, always capable of seeing and nurturing the goodness in others.

Esoteric Buddhism

When the Buddha taught Mahayana Buddhism, he used a great many skillful means to encourage his students to take every moment as an opportunity to develop themselves and move nearer to awakening. The system most emblematic of this approach is that of Esoteric Buddhism, also called Vajrayana, meaning “vajra vehicle.” Esoteric Buddhism is a system of training that focuses on the quick acquisition of “unrevealed” wisdom that cannot be gained simply through study. The methods of Esoteric Buddhism are somewhat mystical in nature and are said to enable one to quickly destroy the impediments of delusion and pierce the difficult to understand nature of reality to gain an inexpressible, direct understanding of it. The precepts, rituals, and practices of this system are only accessible through initiation given by a master who judges when a disciple is ready to receive them. Casual lay practitioners typically do not receive full initiation into these practices, but perform a more limited set of practices, such as mantra recitation and ritual observance of feast days. Priests fully trained and initiated into the Esoteric lineage perform important rites and confer blessings for the community.

“Esoteric” may also refer to the idea that living beings already contain within them the seed of awakening in the form of their intrinsic “buddha nature,” which remains hidden to them because they lack the wisdom to access it. Buddha nature refers to the nature of reality as it relates to one’s own mind. It is the part of us that intuitively sees the shortcomings of the cycle of suffering and aspires to awaken from it. It is our true self and our unlimited capacity to love, find beauty, and experience happiness. Buddha nature is the natural capacity for goodness that all living beings have within them.

The Mahaparinirvana Sutra

After traveling and teaching for nearly fifty years, in the last hours of his life, the Buddha gave his disciples his final teaching in the form of the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, meaning “The Sutra of Great, Final Nirvana.” Both a Mahayana and Theravada version of this sutra exist, but they are quite different in their content. The Mahayana version of the sutra emphasizes using every opportunity to practice, and states that both lay and monastic followers can attain the awakening of buddhahood in this lifetime. For these reasons, it is often considered to be spiritually in line with Esoteric Buddhist teachings, although it is an exoteric teaching. Inspired by the inclusive aspect of this sutra, Shinjo Ito, the founder of Shinnyo‑en, chose the Mahaparinirvana Sutra as the seminal text for the tradition.

The Sutra teaches four key points:

Buddhahood is ever-present: the presence, guidance, and compassion of buddhas is timeless;

All living beings possess a buddha nature: an inner nature that, when awakened to, is buddhahood;

Nirvana is possible for everyone: even the worst of us has within them the potential for enlightenment;

Permanence, bliss, true self, and purity: nirvana is timeless, joyous, personal, and purified of delusion.

The idea that buddhas are “ever-present” is a recurring theme in Mahayana Buddhism. The idea is that the nirvana to which a buddha awakens is neither governed by karma in the world nor fully transcends the world, and that the buddhas are therefore always present to guide living beings toward peace in any way that they can. Given that most of us lack the exceedingly pure karma to meet with a perfectly awakened buddha, the buddhas appear in myriad ways to help living beings—in the guise of ordinary people or even as natural events, such as the wind through the leaves or the reflection of the moon on the still surface of water. Since a buddha in the state of final nirvana is one with the nature of reality, and the nature of reality permeates all of reality including us, the buddha and his awakening is said to permeate each of our hearts and minds as well.

That state of oneness with the nature of reality, nirvana, is permanent, blissful, self, and pure. When one realizes and embodies the nature of reality, one’s existence is no longer experienced as it was when under the sway of delusion and karma—as impermanent, painful, selfless, and impure. Put differently, enlightenment is the realization within oneself of a permanently joyful and pure-hearted self that has clarity of mind and is liberated from egotism. The Mahaparinirvana Sutra emphasizes that this supreme state of consciousness can be attained through practice and that all people have an innate ability to realize it. Master Shinjo taught that we can experience awakened moments of nirvana by trusting and acting in oneness with the ever-present essence of buddhas. This is possible because our own fundamental nature, our buddha nature, is always aligned with Dharma and is intrinsically pure.